An intelligent member of the Catholic middle-class, John Calvin (1509-1564) had the family connections to place him in good schools. He left home in Noyon, France, in 1523, and traveled south to Paris to study law on a church scholarship. There he was exposed to theological conservatism, humanism, and a movement calling for the reformation of the church.

Young Calvin, his name Latinized to Ioannis Calvinus, completed his studies and settled in Paris. He experienced what he described as “a sudden conversion” and joined reform-minded activists who were taking stronger and more public stands on church reform. When his friend Nicholas Cop was installed as rector at the University of Paris in 1533, Cop advocated for church reforms in his inaugural address. Some believed Calvin authored Cop’s controversial remarks, which showed affinities with Desiderius Erasmus and Martin Luther, and Calvin was forced to flee Paris.

The twenty-four year old Calvin relocated to Reformation-minded Basel, where in 1536, he wrote his six-chapter distillation of evangelical faith, published in Latin: Christianae religionis instituto, or Institutes of the Christian Religion. This treatise was systematic and clear. It derived much of its form and substance from Luther’s Kleiner Katechismus (1529) and addressed law, the Decalogue, the Apostles’ Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, the sacraments, and Church government.

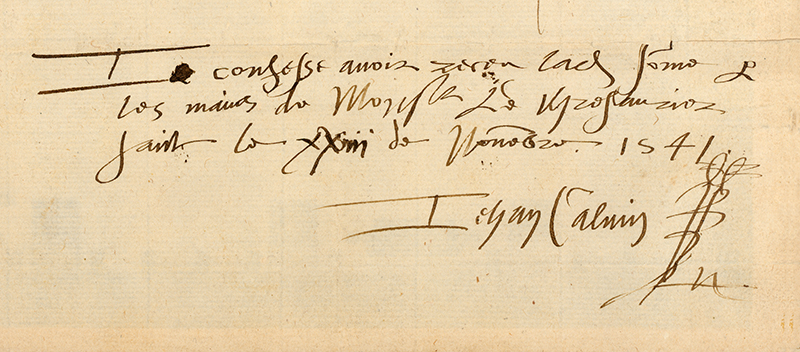

Passing through Geneva later that year, he was persuaded to stay and assist in organizing the Reformation in that city. However, on Easter Day 1538, Calvin publicly defied the city council’s instructions to conform to the Zwinglian religious practices of Berne and was ordered to leave. After serving as pastor to the French congregation in Strasbourg for three years, Calvin accepted an invitation to return to Geneva. In 1541, he began fourteen years of work to establish a theocratic regime in the city, and his Ecclesiastical Ordinances were adopted by the city council in November 1541. These ordinances distinguished four ministries within the church: pastors, doctors, elders, and deacons. Other reforming measures included introducing vernacular catechisms and liturgy.

Over time, John Calvin expanded on and refined his thinking in the Institutes. Responding to the considerable interest in the work and the controversy it generated, he issued a much expanded eighty-chapter version. The text became the most important theological text of the Reformation. The 1559 Latin edition was widely circulated in various forms, becoming the theological source document of Protestantism. The Institutes is hailed as the cornerstone of Calvinist theology.

Calvin’s theology proved to be the driving force of the Reformation, particularly in Western Germany, France, the Netherlands, England, and Scotland. It was from Calvin that John Knox gained the knowledge of Reformed theology and polity that he used as the basis for founding the Presbyterian denomination.