Presbyterian Ecumenists and the Russian Famine

In the period following the triumph of the Bolsheviks in the October Revolution, many American Protestants viewed Russia and all of war-torn Europe as a field for the exercise of mercy. To commemorate the centennial of that momentous 1917, we recall the work of the Federal Council of Churches, and its representative to Russia, the Presbyterian minister John Sheridan Zelie.

In 1919, the Federal Council was chiefly concerned with the maintenance of Orthodox Christianity, establishing that February an ad hoc Committee on Religious Conditions in Russia. Conflict within Orthodoxy would come, but worldly matters took precedence. In 1921, a combination of retaliatory expropriation of peasants' grain storeholds and a drought in the Volga basin brought famine to the war-ravaged Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Having rejected European relief agencies' entreaties for two years, Soviet officials at last permitted entry of foreign relief workers following the New Economic Plan of March 1921.

Accordingly, the Federal Council of the Churches of Christ in America appealed to its member congregations to raise funds for international relief efforts. The FCC's Commission on Works of Mercy and Relief closely coordinated with Herbert Hoover, future president, head of the American Relief Administration. Hoover, himself a vice-president of the FCC, asked American Protestants to view the call for relief in Russia as no different than prior years' calls "for Belgians; for Armenians; for devastated France; for famine sufferers in China."

American Socialists doubted Hoover, claiming he had bragged that he "never fed a Red." American Protestants doubted Lenin. A letter to the Federal Council from the Kansas City Council of Churches describes the conflict. One member of the KCCC's board said "no money should be sent for famished Russia while the present political conditions prevail," and doubted whether any money distributed would not simply be confiscated by the Bolsheviks. The FCC General Secretary responded first that the American Friends Service Committee's work in Russia guaranteed that aid reached its intended targets without "the slightest doubt." As to political conditions:

"We never thought that we ought to allow little children and peasants, who had no responsibility for bringing on either the famine or the present political conditions, to perish."

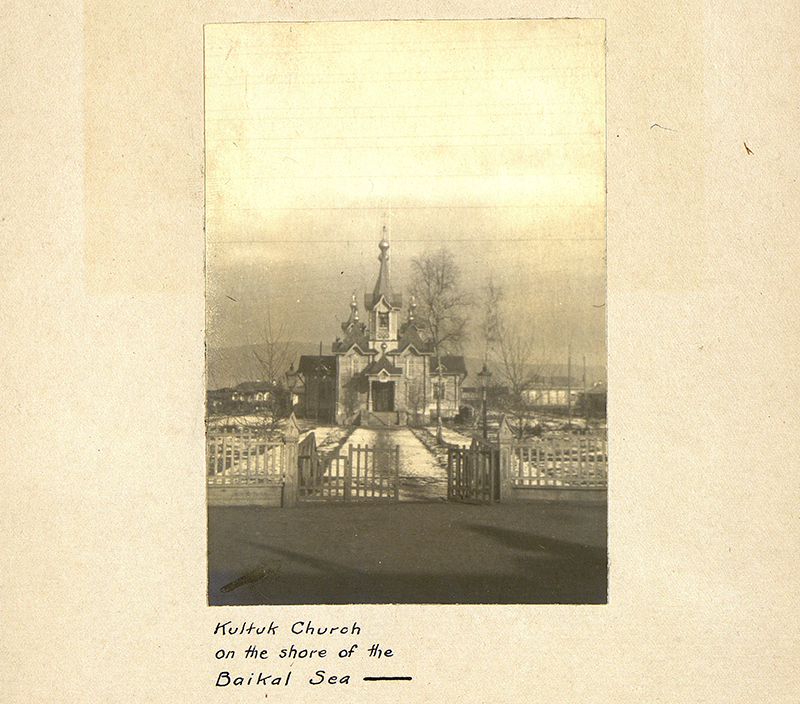

A delegation from the Federal Council to Orthodox Patriarch Tikhon (who had recently been placed under house arrest for refusing Soviet orders to liquidate church assets) had been denied entry to the USSR in May. A representative with a strictly humanitarian mandate was permitted, however, and on June 20 John Sheridan Zelie left New York bound for Moscow. Zelie was well-suited for the work ahead. Born in 1866 in Princeton, Massachusetts, he attended Union Theological Seminary and Yale Divinity School. He served Reformed and Congregational churches in New York and Ohio before joining the United States Army field hospital and ambulance corps, serving as chaplain in four divisions in France from 1918 to 1919.

"It was perfectly clear that I had been sent without any ulterior purpose. They were hungry; we wanted to help them -- that was all." -- J. S. Zelie

Zelie brought with him the second half of the FCC's $121,000 contribution to relief efforts, designated specifically for clergy. ARA staff in Moscow were pessimistic about Zelie's prospects: "My mission was regarded with much dismay owing to the tenseness of the political situation." Working with ARA staff, Zelie traveled to Petrograd, Kiev, and Odessa, delivering the standard $10 package of food -- 50 pounds of flour, 25 pounds of rice, 10 pounds of fats, 10 pounds of sugar, 20 cans of milk, three pounds of tea -- to distressed Orthodox priests, and ultimately to many others. In Petrograd, 126 women, themselves recipients of relief, carried the packages to rural child feeding stations.

Zelie returned to the United States in July. Both he and the Federal Council were cautious not to call attention to the identities of the priests receiving their aid, owing to the ongoing conflict between pro- and anti-communist factions of Orthodoxy. His report to the FCC's Administrative Commission was "vivid and detailed," according to its minutes, but does not seem to have made it into the Council's records. The Presbyterian Historical Society is the FCC's repository; you can browse our holdings of its records here.

Official accounts would put the famine's death toll at 5 million people. Early estimates, by the United States National Information Bureau in the summer of 1923, held that 8 million people would likely be dead by that August. ARA's work would conclude in the middle of June 1923, as the Soviet Union began selling grain in international markets. Schism in the Orthodox Church -- between so-called "Red Priests" who accommodated Soviet rule and Patriarch Tikhon (and ultimately the Orthodox Church in exile) -- would continue to concern the FCC and John Zelie. In August 1924 the head of the FCC Commission on Europe would write Zelie, asking for help in raising $1,500 for the Russian churches in exile in Copenhagen, and asking after his next article in the Atlantic: "I think of you as in solitary meditation on a rocky headland of Maine."

His first article had come in 1921. It was a translation of letters of the Swiss philosopher Henri Frédéric Amiel to a young Nebraska utopian, largely on the perils of communism in agriculture.