Jibrail 1958-1967: Revolution, CROP, and Small Animal Husbandry

November 15, 2017

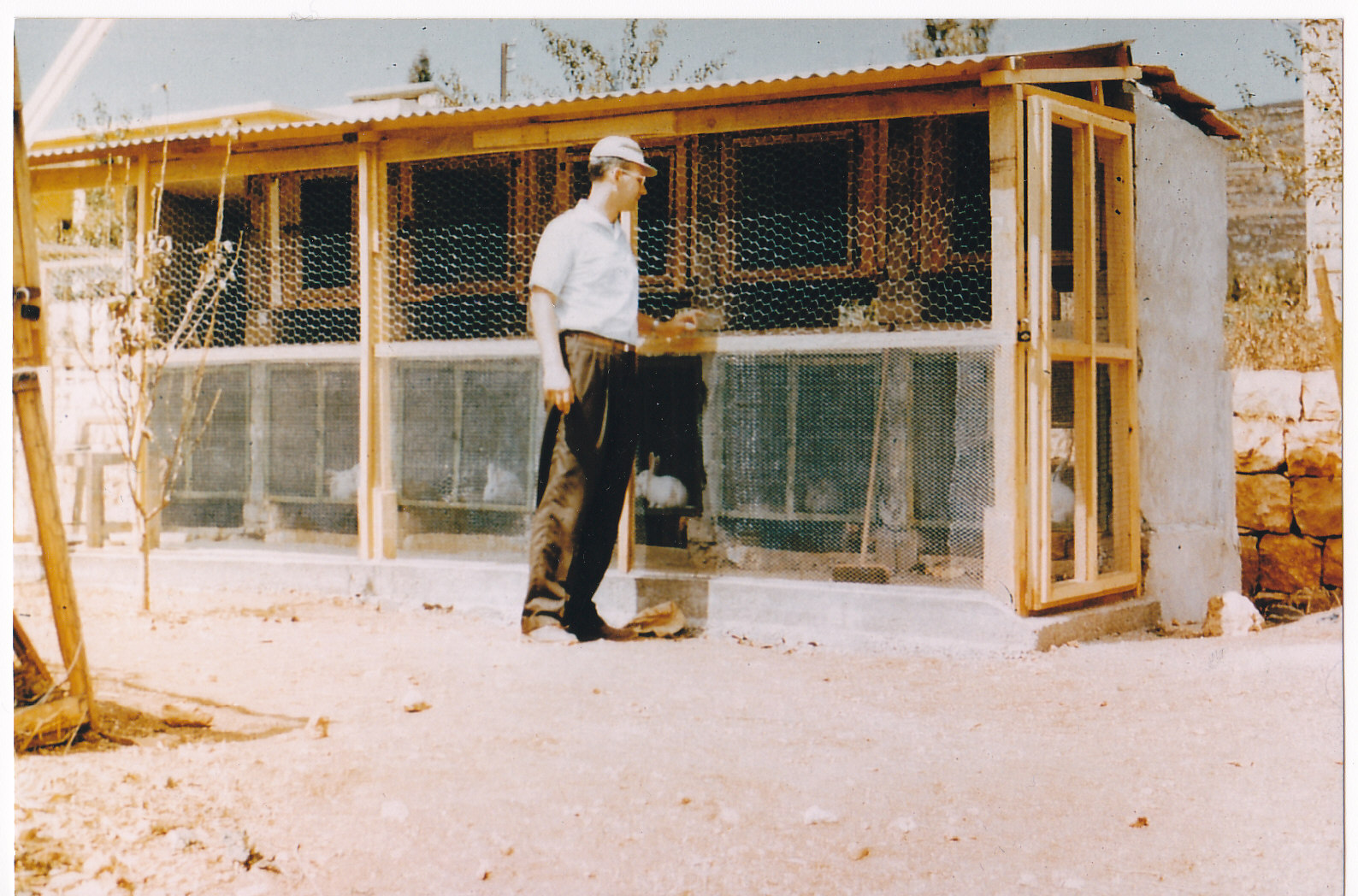

Rabbit house at Jibrail Rural Fellowship Center. Photo courtesy of Phil Hanna.

This is the second installment of a series on rural agricultural work in Lebanon. Read the first installment, Jibrail 1943-1958: An Answer to Communism.

Word to evacuate came in the night by radio, in late May 1958. The Hannas—Ed, Arpiné, their six-year-old son Philip, and Arpiné’s parents, Levon and Josephine Yenovkian—hurriedly packed a jeep and a Ford and fled their two story home. During the previous four years the Hannas had worked with Neale and Edith Alter at the Jibrail Rural Fellowship Center, an experimental agricultural school in remote north Lebanon. Then came the revolution.

Samir Maamary, Neale and Edith Alter, and Ed Hanna speak with village leaders in Jibrail. Photo courtesy of Phil Hanna.

A tide of pan-Arab nationalism initiated by Gamal Abdel Nasser’s successful defense of Egypt in the 1956 Suez crisis peaked in Lebanon in 1958. On 1 February 1958, the governments of Egypt and Syria united to form the United Arab Republic, an event greeted by raucous celebratory marches among young people in the streets of Beirut. Riots erupted in Tyre in late March after five boys were arrested for trampling a Lebanese flag while waving that of the UAR. Lebanon’s president, the pro-Western Camille Chamoun, derided the Nasserites—pan-Arabism was “for some in Lebanon, a source of income, a springboard for attaining cheap popularity, and a stage for dwarfs and mountebanks”—while his foreign secretary Charles Malik asked the Eisenhower administration for military assistance. Lebanon and Libya had been the only Arab states to endorse the Eisenhower Doctrine, and Chamoun cast the pan-Arabists as communist-inspired.

In the early hours of 8 May 1958, the editor of a left-wing newspaper was assassinated. The largely Sunni and pan-Arabist National Front blamed the Chamoun government and called for a general strike. Violence was widespread. In Tripoli sixteen people died in one night during clashes between armed cadres of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party and strike supporters, Druze soldiers of Kamal Jumblatt also attacked the presidential palace at Beit ed-Dine, to be repelled by a rival Druze faction. Intercommunal strife would reach Jibrail.

Ed and Arpiné Hanna, 1957. Photo courtesy of Phil Hanna.

The Hannas had come to Jibrail in 1954, Ed to serve chiefly as Neale Alter’s administrative assistant, and Arpiné to teach in the girls’ school with Edith Alter and the Lebanese teachers Huda Boutros, Salwa Khoury Maamary, and Nuhad Younes Haddad. Ed and Arpiné met in 1949 at a relief center for impoverished residents of Sidon; Ed taught at the Presbyterian Sidon Boys’ School, Arpiné at the Sidon Girls’ School. Arpiné was Armenian, the daughter of parents who fled Turkey for Palestine. She was born in Acre in 1924 and educated at the Ramallah Friends School. The Yenovkians remained in Palestine until 1957, when they decided to join Ed and Arpiné in Lebanon, driving to a remote border crossing between Lebanon and Israel in a car laden with clothes and furniture.

Fleeing Jibrail in May 1958, the Hannas and Yenovkians headed due west for a coastal village. A local authority, the dabit, warned them not to drive to Tripoli overnight and put the family up in his home, buying Ed Hanna’s Ford on the spot. The next morning the Yenovkians caught a cab back to Jibrail to pack some of the things they’d carried from Palestine just the year before, and the Hannas, driving Neale Alter’s jeep accompanied by a Lebanese security detail, made for the Iraqi Petroleum Company installation at Tripoli. They boarded the Jackson Creek, an oil company vessel commandeered by the U.S. Navy to evacuate Americans to Beirut. The Hannas stayed briefly at the American Mission compound in Beirut, then at the American University of Beirut, before returning to Sidon.

Cement block workshop at Jibrail, before 1958. Photo courtesy of Phil Hanna.

A 1959 report on Jibrail by Presbyterian rural work specialist Richard O. Comfort noted that “during the rebellion of last year all the buildings were bombed and looted.” Comfort recommended careful study of whether and how to reopen the agricultural experiment. In any case, “the initiative in these matters should come from Lebanon and not the United States.” Lebanon’s violence remained unresolved. Jim Willoughby, gently dissuading Neale Alter from returning in November 1958, noted that, “No trace has ever been found of Vartan Saghdejian of NEST [Near East School of Theology], who disappeared on one of the last days of the disturbances. The Jessie Taylor Home has been occupied by the Kurds. I do not know what luck the YWCA will have in ousting them.” For its part, the National Evangelical Synod of Syria and Lebanon voted not to reopen Jibrail.

Neale Alter, on furlough in the United States, had other plans. In September 1959, he and Edith attended seminars at the International Cooperation Center in Bozeman, Montana, and at Pennsylvania State University, and Neale began to shepherd potential grant money to Jibrail. The work would be restyled the Jibrail Cooperative Society, and would introduce dairy cattle in north Lebanon, to be funded by the Ohio Christian Rural Overseas Program (Ohio CROP) and Agricultural Missions, Inc. His letters express single-mindedness and overweening hope in equal measure. Munir Khoury and Huda Boutros had not formed a non-profit at Jibrail, a prerequisite for CROP’s distribution of funds, frustrating Alter. Neale found hope in the Synod’s interest in developing a rural parish at Minyara, and noted the arrival of Ben Weir there, counting him a supporter of Jibrail.

Cows at Jibrail. Photo courtesy of Phil Hanna.

Munir Khoury and Huda Boutros had begun ground work for a dairy cooperative at Jibrail, and Jim Willoughby, working with the Near East Council of Churches (NECC), began handling donations from overseas. Though the original Jibrail Rural Fellowship Center had an account in the hands of the American mission of 24,000 Lebanese lira, difficulties in disbursing those funds after the passage of control to the Synod made them “frozen” in Alter’s telling. The chief new contribution to the cooperative came in November 1959 from the Alters’ son Harry, then working in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, as a government relations analyst for Aramco. With Harry’s $350, Willoughby opened an account called “Dairy cooperative,” and soon contributions from Ohio CROP, and from the world service committee of Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church (New York, N.Y.) would fund the project into the summer of 1960. The new money permited teaching at Jibrail to restart, paying former teachers Salwa, Fahad, and Abu Fareed, and a youth, Abdulla.

Through 1960, Alter lobbied the United Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A.’s Commission on Ecumenical Mission and Relations for funding. The Commission gently demurred, suggesting that the NECC fund the project instead. Unofficially, commissioners were loath to fund the new project. On behalf of the Syria-Lebanon mission, COEMAR was still trying to settle claims against it brought by the Khoury family, allies of the Alters and Jibrail's landlords, for lost rent, unfair water allocation, and damage to fruit trees. Jim Willoughby, in an 18 August 1960 letter to Rodney Sundberg at COEMAR, boiled over: Presbyterians should “withdraw immediately from any connection with Jibrail rather than pay what smacked all blackmail.”

Girls tending flower garden at Jibrail Rural Fellowship Center. View in Pearl.

By September, Alter’s relationship with Munir had soured—he wrote to Willoughby of his “extravagant demands” and that Munir was “completely dominated by his scheming mother”—and he looked forward to the return to Lebanon of Samir Maamary, who had completed a B.S. at Ohio State University, funded by an Ohio CROP scholarship. COEMAR would settle Munir’s claims in May 1961 for $2,500, on condition that he have nothing to do with a reopened Jibrail. Khoury would in 1961 be involved with the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP). After a failed coup attempt by SSNP members in Lebanon, he served seven years as a political prisoner.

The patchwork of authority over the projects at Jibrail—accounts held by COEMAR, land owned by the Synod, funding from Ohio CROP routed through NECC, a Jibraili Board of Directors—would be centralized in 1960. Responding to requests from within the Synod to move agricultural work elsewhere in the Akkar Valley, Ben Weir defended work at Jibrail, if only “to avoid at this point the expense of selling one property and buying another, before we know how the project might succeed.” In January the Synod and COEMAR formally transfered control of the newly-styled Akkar Area Cooperative to Ohio CROP. CROP operative Clyde Rogers arrived in Jibrail in the spring of 1961 to secure feed for livestock, begin repairs on the buildings damaged in 1958, and start a poultry program.

Selwa Khoury in National Future Farmer, Fall 1955.

CROP operations in dairy and poultry were extensive. The first transfers of cows and chickens, donated by Ohio Presbyterians, came in September 1961. By the fall of 1962, CROP’s Keith Buchs had established disease eradication, livestock feeding, and artificial insemination programs. In a mid-October letter home he reported the successful sale of cooperative products: “The Volkswagen that left here on Thursday morning was loaded as we had envisioned from the beginning of this project. It had eggs (to be delivered at [Beirut College for Women], rabbits (to be delivered on the road to Beirut), and milk (to be delivered in Tripoli).” On his return, Buchs packed the Volkswagen with “1,100 baby broiler chicks.”

Local tensions spawned by the first Jibrail center re-emerged as the Akkar Cooperative gained steam. In late December 1962, local malcontents cut the water lines to the village, forcing the entire staff, led by Samir Maamary, to spend three days hauling water by hand for the livestock and for themselves; to cope, the cooperative would begin to dig a new well in 1963. The poultry program weathered local opposition, growing to 150 laying chickens and 3,000 chicks. These included “new breeding stock from the U.S. which arrived at 4:00 AM, peeping contentedly after their journey.”

Letterhead of the Akkar Cooperative, from RG 492, box 23, folder 30.

Dairy proved a harder sell. Dairy cattle imported from the United States produced a grade of milk that CROP staff believed was wasted if sold wholesale to leben and labneh producers. CROP staff dreamed of building a pasteurization plant and starting door-to-door milk delivery, and as late as 1964 believed that the dairy program at Jibrail lacked “only better marketing procedures to make a profit.” Though kept afloat by the poultry program, margins for the Akkar Cooperative were never large—it returned $50,000 on expenditures of $45,000 in 1961; $93,000 on $86,000 in 1962; and $228,000 on $223,000 in 1963. And the success of the poultry operation was its own undoing. In 1964, the Akkar region produced 187,000 kilograms of poultry, growing the regional economy by $1 million LL, but by the end of the year markets corrected for this glut, and the price of chicken retreated to the break-even mark. CROP, likely seeing the writing on the wall, negotiated a formal transfer of the Akkar operations in July 1964 to the NECC, represented by Ben Weir. The cooperative strained under debt for chicken feed, and by the summer of 1965 the 17 farmers involved were urged to go it alone. The NECC dissolved the Akkar Cooperative in April 1966 and deeded its Jibrail property back to COEMAR that July. Weir presided over the final sale of the property in April 1967.

Meeting to sell the cooperative, Ben Weir second from left, from RG 492, box 23, folder 30.

Samir Maamary would eventually settle in the United States. Ed and Arpiné Hanna left Sidon for Beirut in 1972, and remained there until 1985, through much of the Lebanese Civil War. Neale and Edith Alter spent 1963 and 1964 working for the UPCUSA to identify affordable housing for retired missionaries; Neale died in March of 1964 in Maryville, Tennessee. Edith retired to Westminster Gardens in Duarte, California in 1967. Two of Munir Khoury’s daughters left Lebanon for Italy.

Nada Khoury, who returned to Lebanon after years in the United Kingdom, retains vivid memories of the cooperative to this day. For the first several years of her father Munir’s imprisonment, she and her two sisters spent the summer with their grandparents in Jibrail, while their mother worked in Beirut. “We hated it: Mom would come and see us during the weekends, but then leave early in the morning Monday mornings to go to work. We got very bored in our isolated house away from the village centre.” Nevertheless, the cooperative held cherished memories for all the Khoury family. Nada's grandmother Marianna, and after his release her father, spoke fondly of the early work at Jibrail, remembering Neale Alter as a strong, guiding influence. Nada and her sisters, and Janan, Samir Maamary’s niece, often played near the cooperative's abandoned buildings, next door to her grandmother's house.

A calf is brought to its mother, Jibrail Rural Fellowship Center, 1956. View in Pearl.

Sources: RG 115; RG 360; RG 424; RG 492; interview with Phil Hanna, April 2017; email with Nada Khoury, September 2017.

See also: Ussama Makdisi, Faith Misplaced: the Broken Promise of U.S.-Arab Relations: 1820-2001 (2010); Karol Sorby, "Lebanon: The Crisis of 1958," in Asian and African Studies 9 (2000); Robert Vitalis, America's Kingdom: Mythmaking on the Saudi Oil Frontier (2009); Mehmet Ali Doğan and Heather J. Sharkey, eds., American Missionaries and the Middle East: Foundational Encounters (2011).