Presbyterians, Catholics, and Northern Ireland: Glorious Revolution to Good Friday Accords

The conflicts that have occurred in the six counties of Northern Ireland or Ulster over the past three hundred years make up one of the most divisive and deadly ethno-religious disputes in modern history. On the surface, the conflict appears to be merely disagreement between the Catholic descendants of “native” Irish and the Protestant descendants of “colonist” Scots and English. But it proves to be emblematic of major questions of tolerance, terror, and nationalism, along with debates on the intertwining of religion and ethnicity, the shifting allegiances of republicanism and monarchy, concepts of “freedom” and “choice,” the earthly limits of religion’s power, and even theological debates at the center of Christianity and its doctrines.

Presbyterians have a special claim in the Northern Irish conflict, as many of the Ulster settlers came from the Scottish-English borderlands, an area which was – and remains – heavily Presbyterian. They were encouraged to settle in the Plantation of Ulster, a large swath of land in Ireland’s north confiscated from the Gaelic Irish by the British king, James I; James expressly wanted to “civilize” the “native” Irish. Many of these settlers repeated their migration and sailed to colonial North America, settling predominately on the frontier of Britain’s colonies in the Appalachian Mountains (“Appalachia”) and building a distinct “Scots-Irish” identity; their descendants still have a strong sense of regional identity and predominate in areas of the Upland South, especially in the state of West Virginia and mountainous areas of Kentucky, Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee. Throughout their history, the Scots-Irish have lived in areas of frontier and flux.

Tensions between Great Britain and Ireland can be traced back almost a millennium, according to some, but the genesis of the most “recent” conflicts originate in the late 1600s.[1] Things reached a head when King James II, a Catholic, began ruling by decree after the English and Scottish parliaments refused to pass his measures regarding religious toleration, as well as the birth of his son, which would have resulted in a Catholic British dynasty. Prince William of Orange, a Protestant Dutch noble and James’s nephew and son-in-law, was invited to Britain by seven Protestant nobles to reclaim the throne from James in return for marrying James’s Protestant daughter, Mary, which became known as the Glorious Revolution. James did not give up, and he remained hugely popular in Catholic parts of Ireland. William invaded Ireland and defeated James at the Battle of the Boyne in County Meath in July 1690. William of Orange was now King William III, and he cracked down harshly on Irish Catholicism and promoted Protestant migration to Ireland. Both Protestant and Catholic settlement and immigration increased in Northern Ireland over the next few centuries, especially in Belfast, which boomed as a hub of shipbuilding and linen manufacturing.

The population of the early United States was overwhelmingly Protestant and largely descended from British settlers. Most enslaved and free African Americans had converted to various Protestant denominations, and European immigrants were primarily from Protestant countries. Despite official decrees of religious tolerance like the Bill of Rights, early America was religiously monocultural, with Roman Catholics making up a tiny number of Americans. It was not until the early-to-mid 1800s that Catholics began coming to America in large numbers, largely from Europe. This sudden wave of Catholic immigrants would pump new life into latent religious tensions dating back to the Reformation.

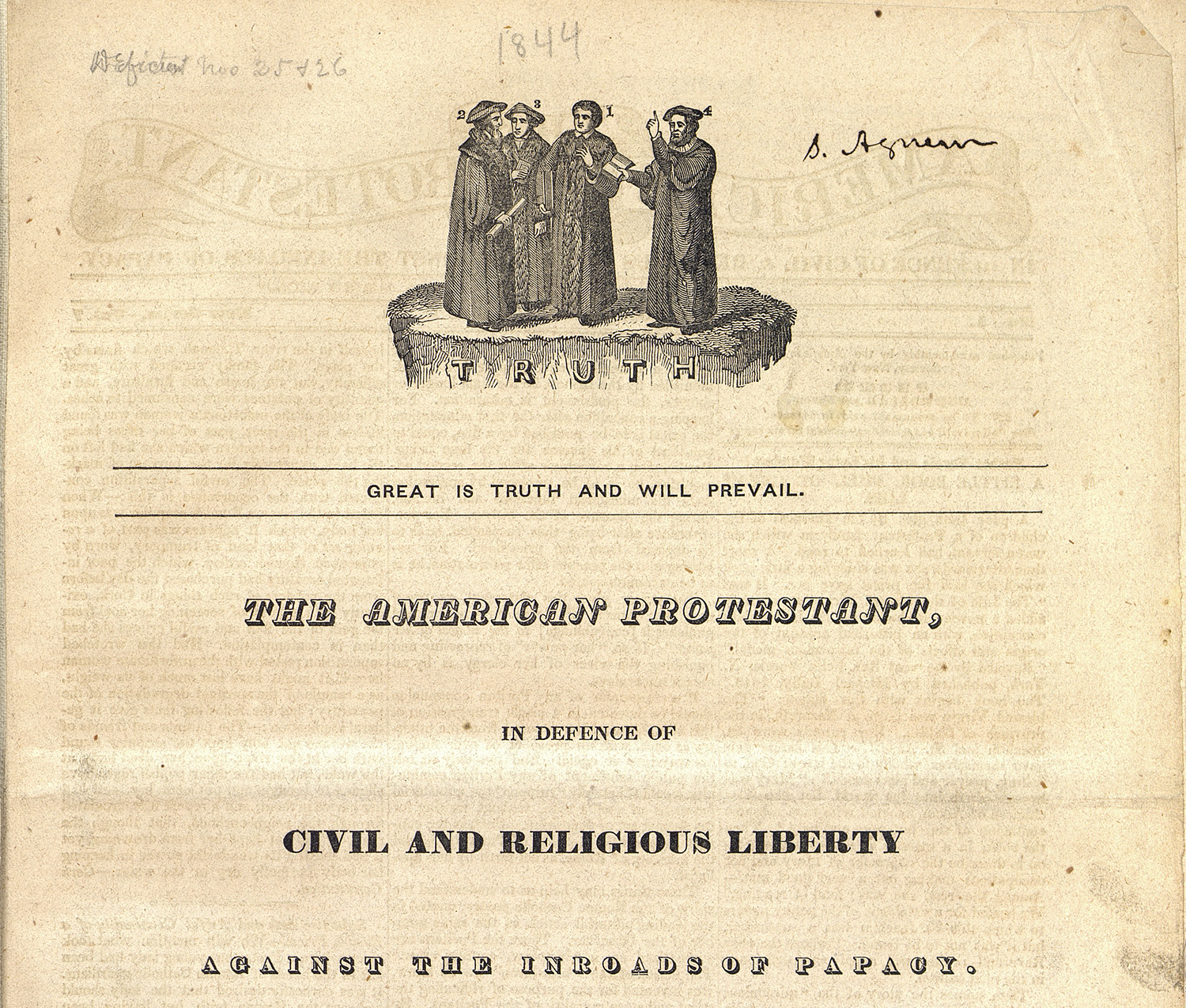

Anti-Catholic writings of the nineteenth and twentieth century in America combined theological concerns with xenophobia and the ideals of the “American project.” The Catholic Church was viewed as an interloper in Protestant America; Protestantism and American “freedom” and “liberty” were viewed as going hand-in-hand, and secularists feared that Catholic immigrants held more fealty to the Pope than to the US government. Through its veneration of the Papacy, the Virgin Mary, the saints, and holy relics, the Catholic Church was accused by Protestant extremists of “worshipping” beings and objects which Protestants viewed as secondary to God.

One such propagator of anti-Catholic rhetoric was the American Protestant Association, which was founded to oppose Catholic immigration. The minutes of their conferences reveal religious prejudices that shock and upset many today. One speaker claimed that the statue of St. Peter in the Vatican was merely a statue of the Roman god “Jupiter Capitolinus” with the head of St. Peter attached, and that it was worshipped as an “idol” just as the ancient Romans had. Another speaker, one “Mr. Newton,” claimed that Catholicism was the reason why the countries of South America were less developed than the United States. In Newton’s view, North America by all rights should be a backwater compared to resource-rich South America; he also injected contemporary attitudes towards Native Americans, describing the indigenous inhabitants of North America as “….warlike, hostile tribes” and those of South America as “peaceful, quiet, and manageable….ready to render any service to their rulers.” Instead, the United States stretched across the continent and commanded the attention of world powers, whereas the various nations of South America never united and squabbled over land and resources. This was blamed on South America being majority Catholic: “....the South must trace all her weakness and misery to Popery.” Another propagandist was the Protestant Vindicator (sometimes published as The American Protestant), a New York-based newspaper which combined regular news and features with anti-Catholic, xenophobic polemics like this:

“Do they not know that the Jesuit and Dominican priests of Europe do hold a weekly concert of prayer, and celebrate high mass each Wednesday, to move heaven to help them in converting Britain, and the United States, to the good old religion of Holy Mother Rome? Do they not know that in seven or eight years, the votaries of Rome and idolatry have increased in our U. States, from 600,000, to ONE MILLION AND EIGHT HUNDRED THOUSAND? And do they not know that these hundreds of thousands, are regularly trained, and officered as a vast army, and kept as distinct from Protestants, and native citizens, as the Jews keep themselves distinct from Christians?”

Such charged language would result in civil disturbances like the 1844 Philadelphia Nativist Riots, where Protestant mobs tore through Philadelphia and its surrounding townships, killing Catholic immigrants and burning down their churches. Even later, in 1870 and 1871, the Orange Riots broke out in New York on July 12, with clashes between Irish immigrant Catholics and Protestants in Manhattan leaving over sixty dead.

As Catholics assimilated into American society, tensions between them and Protestants died down. However, outbursts of anti-Catholic sentiment continued into the mid-twentieth century. Religion was used to tar Democratic presidential nominees Al Smith in 1928 and John F. Kennedy in 1960. Even as late as the 1950s, the pamphlet “Are You an Orangeman?,” a heavily anti-Catholic writing with a bright orange cover, was distributed to congregants in a Presbyterian church in New Jersey.

In the 1960s, tensions were inflamed once more in Northern Ireland as Irish Catholics, inspired by African Americans in the United States, protested for their civil rights. Protestants in Northern Ireland tended to support the British crown, while Catholics tended to prefer the Irish Republic to the south (The two populations each make up roughly half the population of Northern Ireland, thus increasing tensions). This ethnic and sectarian conflict gradually spiraled out of control, as the Northern Irish authorities took a hard line against Catholic protestors, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) was revived, protestors were detained in prisons, security checkpoints were established, and Loyalist militias began rising once more. This period, known as “the Troubles,” consisted of everything from riots to bombings to hunger strikes and resulted in over 3,532 dead. The violence reached its peak in the 1970s and 1980s, before tapering off slightly in the 1990s as the British, Irish, and American governments worked to establish a peace agreement for Northern Ireland. The end result was the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 (partially brokered by the USA), which established conditions for peace in Northern Ireland and largely resulted in the cessation of widespread violence in Northern Ireland. The agreement was heavily backed by American Protestants and Catholics, including Presbyterians, who were particularly instrumental in the peace process due to the heavily Presbyterian population of Ulster.

The border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland is officially semi-porous, with few to no border checkpoints so that Catholic citizens in Northern Ireland may freely visit their families in the Republic. More ominously, “peace lines” extend across swaths of Northern Irish cities and towns; these are barriers meant to keep Protestant and Catholic populations separated in potentially sensitive areas where they reside close together. Recently, however, the process of Brexit has thrown the Good Friday Agreement – and the future of peace in Northern Ireland – into question once more. If the United Kingdom leaves the European Union, a “hard” border could soon exist between Northern Ireland the Republic of Ireland, thus violating the terms of the agreement. Meanwhile, tensions have flared once more between Catholics and Protestants. It seems that, even as Presbyterians – and nations as a whole – have evolved on the question of Northern Ireland, the situation itself, once seemingly settled, continues to return with a vengeance.

-- Anthony McDonnell is a summer intern at the Presbyterian Historical Society. A recent graduate of the Community College of Philadelphia, Anthony will be enrolling at Temple University in the fall of 2019. His work is a part of the Building Knowledge & Breaking Barriers project. You can check out his other posts here.

Further Reading

Pearl collection materials related to Northern Ireland

Sheppard collection materials related to Northern Ireland

[1] After Oliver Cromwell’s death, the House of Stuart, whom he deposed, resumed control of the throne under King Charles II; upon his own death, his brother ascended to the throne as King James II. James was immediately controversial due to his private Catholicism and his strong belief in “the divine right of kings.”