John Bingham: Preeminent Lawmaker, Esteemed Diplomat, Presbyterian Layman

--by Sam Kidder

In a New York Times opinion piece in 2013, constitutional law scholar Gerrard Magliocca wrote, “More than any man except Abraham Lincoln, John Bingham (1815-1900) was responsible for what the Civil War meant for America’s future.”[1]

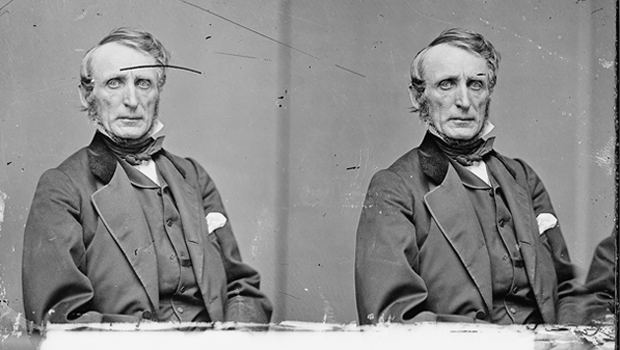

While a Congressman Bingham served as lone civilian prosecutor in the military tribunal for the Lincoln assassins; delivered the House impeachment articles to the Senate in the trial of President Andrew Johnson; and authored key sections of the Fourteenth Amendment. It is this contribution to America’s constitution that has led him to be called “the American Founding Son"[2] or “the Second Madison.”

After a remarkable career on Capitol Hill, Bingham also assisted four presidents as America’s longest-serving chief diplomat to Japan. And yet history has largely ignored this accomplished Presbyterian. In this two-part series, I will discuss Bingham’s domestic and foreign service, as well as the Presbyterian influences that shaped his worldview.

In western Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio where he was born and grew up, Presbyterian preachers were among the educated elite of many small, burgeoning communities. John Bingham was born in 1805 in Mercer, Pennsylvania, where his father, Hugh, was active in the local Presbyterian church. The Reverend Samuel Tait, a pastor in the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A., had come to Mercer County in 1800 and would remain there until his death in 1841. For four decades Tait’s association with Hugh Bingham was constant and close.

Hugh Bingham joined with Tait to form a local missionary association under the leadership of the American Board of Commissioners of Foreign Missions (ABCFM). In 1820, Hugh Bingham is listed as Secretary of the newly formed Mercer chapter of the American Bible Society, which boasted John Quincy Adams and Francis Scott Key among its long list of distinguished vice-presidents.[4] Tait and the elder Bingham clearly shared an interest in institution building beyond the demands of a local pastorate.

In Cadiz, Ohio, where John Bingham lived for a time with this uncle’s family after his mother’s death, and later as a student at Franklin College[5] in New Athens, Ohio, young John Bingham was strongly influenced by Reverend John Walker. Walker was the intellectual mainstay of Franklin and an ardent anti-slavery crusader who maintained an Underground Railway station. During his college years, John Bingham began a life-long commitment to racial equality and, significantly, developed a longstanding friendship with Titus Basfield, a former slave and fellow classmate.[6]

During his years in Congress, Bingham combined moral commitment with practical legislative acumen. In the immediate post-Civil War years, he served as lone civilian prosecutor in the military tribunal for the Lincoln assassins. Bingham delivered the House impeachment articles to the Senate in the trial of President Andrew Johnson, and provided the trial’s closing argument, an oration that stretched into a third day. And most notably, he was the primary author of the key sections of the Fourteenth Amendment, language that—after generations of neglect—became the legal underpinning of the civil rights movement and the struggle to apply “equal protection” and “due process” to all Americans.

After losing his reelection bid in 1872, Bingham was appointed by President Grant to be Minister[8] to the Empire of Japan. Unlike many diplomatic appointees both then and now, Bingham was not a wealthy man. He needed an income. And he wanted to continue to serve.

While still in Congress, Bingham had become aware of the problems and potential of Japan as a partner for the United States. America had only recently become active in the Pacific with the purchase of Alaska in 1867, the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, and renewed missionary interest in Japan now that the civil war had ended. On a personal level, Bingham had a close family friend, a young Presbyterian missionary, David Thompson, who had arrived in Japan in 1863. From the same small Ohio hometown, a member of the same church, and a graduate of Bingham’s alma mater, Franklin College, Thompson was to play a major role during Bingham’s years in Japan.

In 1871, Thompson led a small group of young Japanese to the States and then to Europe.[9] Then, in 1872, a large delegation of Japanese spent weeks in Washington, D.C., as part of the first major diplomatic initiative of Japan’s new Meiji government. Japan was remote to Bingham, but through personal and professional contacts such as Thompson, the ancient society was not unknown.

As soon as he arrived in Japan in September 1873, Bingham began to transform America’s relationship with Japan’s new Meiji government, which had recently thrown off centuries of rule by Tokugawa’s military rulers. He pushed for policy changes to address Japan’s legal and practical subordination to the Western powers. Inheriting a legation that was poorly housed and staffed, he put America’s diplomatic presence on a firm institutional footing. And, perhaps most importantly, he acted as mentor to the generation of American Japan experts who would continue to influence America’s bilateral ties with Japan well into the mid-20th century. I will cover some of these accomplishments in the second and concluding post in this series.

--Sam Kidder is a member of the session of Bower Hill Community Church in Mt. Lebanon, PA. He studied East Asian history as a graduate student at Harvard and the University of Washington before entering the Foreign Service, where he had assignments in Korea, Japan, and India. He now works with his wife Miyako doing public relations and editing work, mostly for Japanese clients.

Learn more

Read about David Thompson and his years in Japan in the Missionary Calling blog series by PHS, which features edited transcriptions of the diaries of Thompson’s wife, Mary Parke Thompson.

The only recent and complete biography of Bingham is by Indiana University School of Law Professor Gerrard Magliocca. Click here for the book’s NYU Press publication page.

[1] New York Times, September 17, 2013.

[2] Magliocca, American Founding Son, New York University Press, New York, 2013.

[3] Bingham and Stevens were House managers and at the time; Stevens was very ill and is pictured with a cane.

[4] Annual Report of the American Bible Society, 1820, p. 22. Adams was a strong anti-slavery voice. Key was himself a slave owner and in the 1830s began freeing his slaves.

[5] Franklin College formally closed in 1919.

[6] Walker belonged to the Associate Reformed Presbyterian denomination. In Cadiz, John Bingham’s uncle Thomas was an important member of the Associate Reformed congregation. The Associate Reformed and the Associate Synod of North America denominations united in 1858, becoming the United Presbyterian Church of North America. See the Family Tree of Presbyterian Denominations for more.

[7] Franklin College ceased operations after over a hundred years of teaching Ohio’s young people, both men and women. Graduates included two governors, eight United States Senators, and nine Congressmen.

[8] At that time, the title for America’s senior diplomatic representative to Japan and many other nations was Minister. The position was upgraded to Ambassador in the early twentieth century.

[9] To learn more about David Thompson and his years in Japan, see the Missionary Calling blog series by PHS, which features edited transcriptions of the diaries of David Thompson’s wife, Mary Parke Thompson.

[10] After traveling to the States from Japan, David Thompson (center rear) escorted the group of young Japanese to Europe as well. On the back of the photo are the names of the group. (Left to right, back row: Kagawa, David Thompson, Niwa. Front row: Ban, Hoshiai, and Tsuda.) Only surnames are given but, interestingly, the regions of origin are noted. The characters used for the regional divisions were the old ones and were revised with the new Meiji government’s centralization policy. Bingham’s time, whether in the United States or in Japan was a time of dramatic social change in both societies.